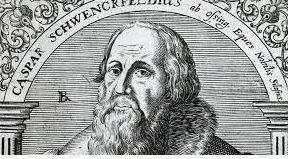

Caspar von Schwenckfeld

Caspar von Schwenckfeld (1489–1561) was a German theologian and an important representative of the 16th-century religious reform movement, which distanced itself from both the Catholic Church and the Lutherans and Zwinglians. He is best known for his Schwenckfeld movement, which was characterized by its own distinct Christian theology and spirituality and continues to exist today as one of the small Protestant movements.

Early Life and Education

Caspar von Schwenckfeld was born in 1489 in Olbersdorf, near Zittau (in present-day Saxony, Germany). He grew up during a time when the Catholic Church and social structures were being challenged by religious reform movements. Schwenckfeld studied law and theology at the University of Leuven and became familiar with the theological developments of his time at an early age.

Relationship to the Reformations

Schwenckfeld was initially a follower of Martin Luther, but over time he developed into a critic of the Lutheran Reformation. While Luther advocated a radical separation from the Catholic Church and a return to a scripturally oriented theology, Schwenckfeld had his own ideas about Christian practice and theology, some of which differed from Luther's.

A central theme in Schwenckfeld's theology was the doctrine of grace and the inner renewal of man, which he emphasized more strongly than the Lutheran concept of justification by faith alone. Schwenckfeld believed that grace and sanctification required a deeper, more personal experience than those practiced in the Lutheran and Catholic churches. This emphasis on inner transformation and sanctification led him to distance himself from official Lutheran doctrine.

The Schwenckfeld Movement

The Schwenckfeld Movement, which he founded, represented a mystical and pietistic form of Christianity that found followers primarily in the regions of Upper Lusatia (near Zittau and Görlitz) and in southwestern Germany. The Schwenckfelds rejected the sacramental teachings of the established churches and emphasized inner, personal access to God.

An important point of Schwenckfeld's theology was the rejection of the Lord's Supper as a physical act. Schwenckfeld viewed the Lord's Supper not as an external ritual act, but as an inner, spiritual union with Christ. He emphasized the Spiritual Presence of Christ and emphasized that this presence was found primarily in the heart of the believer and not in material acts.

Schwenckfeld's Theological Positions

Rejection of the Lutheran "bread" in the Lord's Supper: Schwenckfeld rejected the Lutheran notion of the corporeality of Christ in the Lord's Supper and instead emphasized the spiritual reality of communion. This led to tensions between him and the leading reformers of his time.

The Doctrine of Grace: Schwenckfeld held that the grace of God was not a one-time gift, but that man must continually receive divine grace to live in a holy relationship with God.

Relationship between Christianity and the world: Schwenckfeld emphasized a rather ascetic attitude toward the world and earthly goods. He placed great value on inner enlightenment and spiritual practice.

Mystical spirituality: His theology was characterized by a mystical piety that was strongly linked to medieval mysticism. Schwenckfeld emphasized the importance of experiences of the divine presence and the inner experience of God.

Rejection of image veneration and the Catholic sacraments: Schwenckfeld rejected Catholic sacraments such as the Eucharist and confession, as well as the veneration of saints. He also rejected the veneration of Mary as unbiblical.

Religious tolerance: Schwenckfeld advocated religious tolerance and attempted to build a bridge between the various Protestant denominations, even while distancing himself from the Lutheran and Zwinglian reformers.

Conflicts with the Other Reformers

Schwenckfeld was in constant conflict with other reformers, especially Martin Luther and Philipp Melanchthon, who rejected his theology as too unorthodox and mystical. His rejection of the bodily presence of Christ in the Lord's Supper, in particular, led to sharp disputes. Schwenckfeld was heavily criticized by Lutheran theologians and excluded from the Lutheran Church and the Reformation in general.

Schwenckfeld, however, had a closer relationship with the Radical Reformation, particularly with the Anabaptists, whose rejection of the state church and emphasis on inner religious experience reflected his own views. Nevertheless, Schwenckfeld's movement differed from the Anabaptists in that Particularly in his rejection of Anabaptist baptism and his less radical stance.

Later Life and Death

Schwenckfeld spent most of his life in exile, as his religious ideas were rejected by both Catholic and Lutheran authorities. Despite this isolation, he remained active in his theology and writings. He died in 1561 in Strasbourg, where he spent a large part of his final years.

Legacy and Influence

After his death, the Schwenckfeld movement initially disappeared from Germany, but Schwenckfeld's followers later found refuge in other countries, such as the United States, where they were particularly present in the Pennsylvania region. Even today, Schwenckfeld congregations continue to cultivate his spiritual and mystical theology, although this movement is very small and currently rather marginal.

Schwenckfeld's influence is particularly noticeable in the areas of Pietism and mysticism, and his emphasis on inner renewal and personal experience of God had an impact on the subsequent development of Protestant faith, particularly in the Radical Reformation and Pietistic and mystical thought.

Summary

Caspar von Schwenckfeld was an influential but often misunderstood reformer of the 16th century. With his mystical, spiritual, and inwardly oriented theology, he opposed both the Catholic Church and the Lutheran and Zwinglian Reformations. His movement, the Schwenckfeld Movement, emphasized inner renewal, grace, and personal connection to God, leading to a religious orientation that distinguished itself from established traditions. Schwenckfeld's influence lives on in smaller religious communities, and his ideas shaped the development of Pietistic and mystical thought in Protestantism.